Let’s look at the effects of stress on the body

Each of us have a different threshold for feeling “stressed” yet most would agree it is not a comfortable feeling.

While we may think we “know” when we are stressed, this is not always the case.

An aroused, or stressed, state is reflected physiologically in 3 of your body systems:

- Your hormones

- Your immune system

- Your sympathetic nerve system

Hormonally, cortisol and adrenaline are released when you are stressed.

This can cause high blood pressure and high blood sugar levels. Cortisol has also been implicated in contributing to fat deposits around your abdomen.

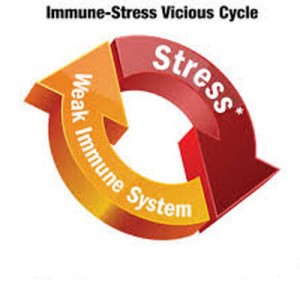

Stress and your Immune System

Your immune system can be adversely affected by stress. The classic example is the increased frequency of viral illnesses that marathon runners experience after a race. Even ‘good stress’ can have negative implications for the body!

Whilst a strong link between cancers and chronic stress has not been established, there is emerging evidence that chronic severe stress is implicated in healing (or lack thereof) of established cancers and possibly in the onset of cancers.

NOTE: There is a more established link with coronary artery disease and stroke risk.

When over activated the sympathetic nervous system can reduce heart rate variability.

This is mediated, in part at least, by the third body system – the sympathetic nervous system – which, if over activated, leads to high blood pressure, high heart rate and reduced heart rate variability.

The impact of chronic stress

Chronic stress is linked to an increase of cholesterol laden plaque inside the arteries (atherosclerosis) and hence a higher risk of heart attack and stroke.

If stress is damaging our bodies by causing heart attacks, strokes and maybe cancers, how can we best measure it?

We can ask people “do you feel stressed?”A standardised questionnaire called DASS (Depression, Anxiety, Stress Score) does have some usefulness.

Measuring the unseen damage of stress

It might be more convincing to have a test that captures physiological arousal and hence damage to the body as well.

It is possible to measure the effects of stress indirectly by measuring:

- Blood test markers which reflect inflammation and to some extent organ damage. One model from the US has been commercially available for approximately $300.

- Cortisol levels in the saliva. However there are technical issues in timing, collecting and handling the samples let alone the interpretation so this is not especially “user friendly“.

- Skin conductance but this would require a commercially viable tool (I am trialling one at the moment).

Heart Rate Variability Assessment

The Heart Rate Variability (HRV) assessment is the best method I’ve seen to measure stress.

This is a fancy term for an ECG performed at rest over several minutes with complex software to determine whether you are in “sympathetic” (arousal/stressed) mode or para-sympathetic (relaxed) mode.

Some of the advantages of Heart Rate Variability testing

What is impressive is that there is extensive literature on heart rate variability and it’s robustness in measuring physiological stress – and its predictive value in highlighting future risk of heart disease. Hence it is both measurable and predictive.

This testing can be performed on site and interpreted at the time of testing.

Most importantly, we can intervene and teach people how to manage their stress better (there is robust evidence that this works) which in turn reduces psychological illness, the risk of heart attack and stroke, and likely other long term illnesses as outlined above which reduces your long term health risk.

Having extensively researched the technology, Executive Medicine will be introducing the Heart Rate Variability Test in our practice over the next couple of months.

This is an ideal way for you, or your organisation, to “keep a pulse” on stress levels. It allows us to see if there are more manifestations of stress, and hence damage, than might be apparent thus enabling earlier intervention to save lives.