Recently an article in the Wall Street journal talked about a young woman, a chef in a Michelin starred restaurant, who treated her anxiety with modifying her diet – more whole grains, leafy greens, avocado and nuts. She improved.

So, is there a connection with what we eat and how we think and feel?

A Western dietary pattern has been found to be associated with an increased risk of depressive disorders or symptoms. For example, a large study indicated a relationship between lower fruit and vegetable consumption and an increase in distress levels. Previous research has linked anxiety as well as depression with unhealthy dietary patterns. The SUN cohort study followed 10,094 university students for 4 years and found those with the highest adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern (which we promote within our practice for its 30% reduction in stroke and heart attack) showed a >30% reduced risk of developing depression over the study period – compared with participants with the lowest adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern. Studies of traditional diets in Japan, Norway and China have found similar results.

There have been 2 intervention studies in the last 12 months suggesting that dietary modification may prevent depression. One study was a follow on from the Mediterranean diet in that those who adopted the diet including boosting nuts, showed a strong trend for the prevention of new cases of depression. In another US study, dietary intervention was just as effective as psychotherapy in reducing the transition rate from mild depressive symptoms to full blown depression.

Finally, The SMILES (Supporting the Modification of Lifestyle in Lowered Emotional States) trial, the first randomised controlled trial of a dietary intervention to treat major depressive disorder, found that prescribing a modified Mediterranean diet as an adjunctive treatment resulted in 31% achieving remission compared with a placebo and a number needed to treat of 4.1.

Why and how?

Researchers believe that depression is not just a thinking or mood disorder but may be a whole-body disorder involving the presence of:

- Generalised chronic inflammation,

- The immune system,

- Our gut flora.

Our brain is strongly influenced by the level of generalised inflammation (if present) within our body, the type of gut flora we harbour (our gut has more serotonin than our brain for example) and the integrity of our immune system.

The ‘typical Western lifestyle’ left unchecked, is thought to cause a chronic low-grade inflammatory state within our body – the same inflammation that precipitates heart attacks due to arterial inflammation. The Western lifestyle risk factors include: a poor diet, lack of sleep, being overweight and chronic stress.

Many of these factors also influence the composition of our gut flora (i.e. the microbiome), which is being recognised as a possible key player in the regulation of mood, cognition and anxiety, as well as influencing our immune system. Our gut flora influences multiple body systems including: brain function, weight management and metabolism, and thus overall health.

There are 2 ways in which our diet can interact with our immune system, gut flora and brain:

- Not eating enough of nutrient dense whole foods such as green leafy vegetables, whole grains etc leading to a detrimental effect on our immune system, genes expression and make-up of our gut flora,

- Eating too much of saturated fats, processed foods and sugars (particularly found in out of home foods – take-away meals, restaurant foods etc.). These food groups have a negative effect on brain proteins (neurotrophins) which promote brain cell growth (neuroplasticity) and also protect the brain cells against oxidative stress.

There is extensive evidence in animal studies that manipulation of the diet manipulates the function of the hippocampus (a structure deep within the brain which is central in new learning and memory deposition as well as mood). In human adults, the size of the hippocampus is linked to the quality of one’s diet.

So, what should we eat?

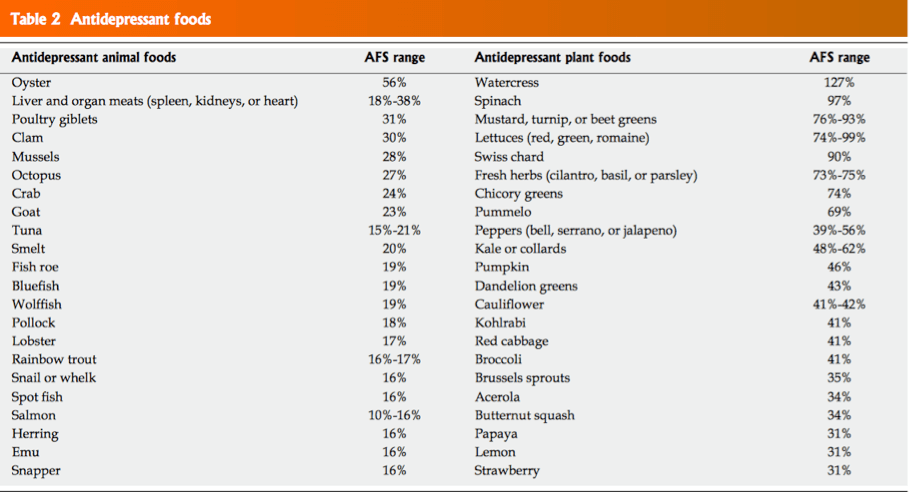

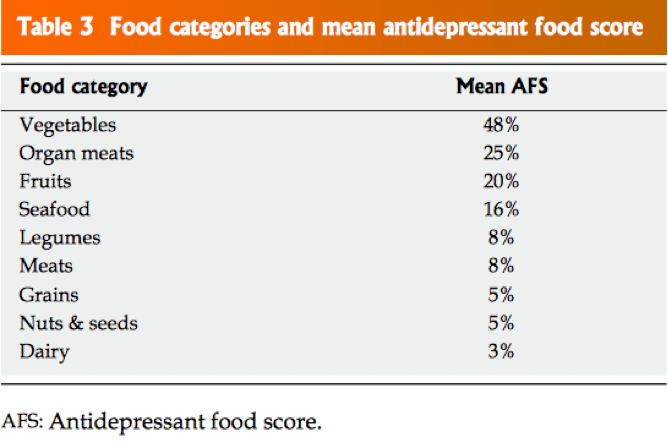

A publication in 2018 in the World Journal of Psychiatry aimed to investigate which foods contain the most dense sources of nutrients demonstrated by the scientific literature to play a role in the prevention and promotion of recovery from depressive disorders.

The publication came up with a range of foods with relative strength of antidepressant properties, ranked according to the Antidepressant Food Score (the higher the number the more potent the food). Interestingly, top scoring foods on the AFS; seafood, leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables, and nuts, are commonly consumed as part of a variety of traditional diets.

The recommendations for all of us include:

- Eat many more vegetables / salads: 5 cups a day equivalent incorporating high AFS types (see above). Nutrition Australia recommends 5 Cups per day for women and 6 Cups per day for men.

- Fibre is key – gut microbiota act to influence health by fermenting fibre and the more fibre the healthier our biome. The CSIRO Healthy Gut Diet book has great suggestions and recipes.

- Increase seafood – the US Dept. Of Agriculture estimates that 80-90 percent of the population fails to meet the recommendation of two servings of seafood per week.

- Experiment with organ meats – liver, kidney, lung etc. These are traditional Northern Hemispheric foods which are not eaten much in Australia.

- Boost legumes (chick peas, lentils, beans etc.) Again this is not much practiced in Australia.

- In terms of gut biome, vinegars such as balsamic and apple cider also appear to be very beneficial to the gut, as are fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha and tempeh etc.

- Eat wholesome nutritious foods for every meal and snack.

- Start small with sustainable changes.

- Limit your intake of ultra-processed foods, alcohol, high fat, high salt and also sugary foods to once a week maximum.

What about supplements?

There also seems to be a role for nutritional supplementation in some people under certain circumstances. For example:

- Omega 3 fatty acids, found in fish, appear to be helpful for people suffering from quite serious depression.

- Zinc or vitamin B supplementation may be helpful for some. There is also a lot of animal research that points to zinc as an important nutrient in mental health. Zinc supplementation appears to be helpful for depression in conjunction with other treatments, while dietary zinc intake is also protective for depression in the population.

- There is also an amino acid called N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) that has been shown to be particularly helpful for people with depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorders.

In summary

Diet and nutrition are as relevant to brain and mental health as they are to physical health.

Find out how your diet is impacting your health. Book in for a health check here.